Next Year / L’Année Prochaine / 明年

Mixed media installation featuring a single channel HDvideo (17:40min)

2016

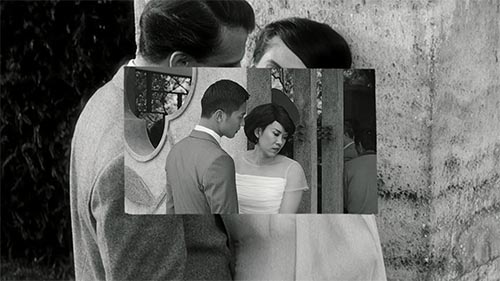

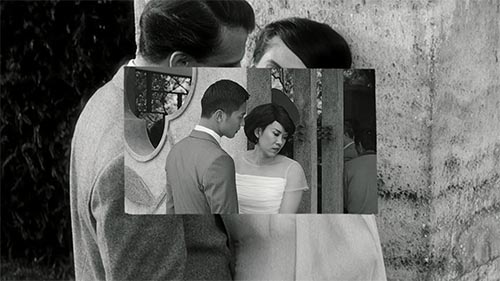

video preview

“With Next Year / L’Année Prochaine / 明年, Singaporean artist Ming Wong revisits an icon of the French New Wave: L’Année dernière à Marienbad (Last Year at Marienbad, 1961) by Alain Resnais, written by Alain Robbe-Grillet. This film is still famous for the ambiguity of its narrative structure and its innovative cinematic language. The camera reflects the pace of the mind through repetition, reversal, freeze frame, and captures reality, memory, and illusion while inventing a sequential order different even from the internal logic of the montage.

Next Year / L’Année Prochaine / 明年 is no remake of the original movie, but a variation on the unequivocal shift desired by Resnais. Ming Wong emphasizes and confirms the loss of temporal and spatial markers by engaging in a dialectical and iconographic collage.

This work is the second version of the piece initially produced for Ullens Center for Contemporary Art in Beijing in 2015. In the first version shot in the French Concession district in Shanghai, the artist performs both male and female characters. Notions of identity and gender fade as much as assert themselves in a strange and complex atmosphere. This time, a new editing combines the existing new scenes with new shots at Nymphenburg and Schleissheim Castles in Bavaria – where the film was originally shot in 1961, excerpts from the original film and from Hiroshima, mon amour (1959, by Resnais as well, written by Marguerite Duras) shot in Japan and in the streets of French city Nevers.

Between the meanders of time and forgetfulness advocated by L’Année dernière à Marienbad and passionate love inhabited by Atomic anxiety in Hiroshima, mon amour, this referential collage ignores the sacrosanct rule of unity of time, action and space. Representation and narrative levels meet there, overlap and blur. The result is a floating, dreamlike and pointedly artificial universe in a pure Dadaist logic that overcomes the notion of authorship and affiliation of the work.

The space of Next Year / L’Année Prochaine / 明年 is not real but mental. It’s colluding different realities and fictions to produce what Max Ernst called the “spark of poetry that arises from the approximation of the realities.”

Text by Étienne Bernard, director/curator of Passerelle Contemporary Art Center in Brest, France, where this work had its premiere.

“In 明年 | Next Year | L’Année Prochaine, Ming Wong performs the male and female roles in fragments taken from Last Year in Marienbad (1961), written by Alain Robbe-Grillet and directed by Alain Resnais. The film is celebrated for its innovative cinematic language – the camera reflecting the pace of the mind through repetition, reversal, freeze frame, and white out-capturing reality, memory, and illusion while inventing a sequential order different even from the internal logic of the montage.

In the original film, the memory loss of the main character inhibits her thought process and time-”next year” compressed into now-loses all meaning.

Ming Wong’s video works are generally based on excerpts of art films. From beginning to end, Last Year at Marienbad never makes reference to a specific location, and Ming Wong takes advantage of this fact to re-stage the work at Marienbad Café and Fuxing Park, both in Shanghai. Taking place in a café named after a French art film and a park combining French and Chinese gardening styles, neighborhoods and apartments that reference Chinese and Western architecture, the film hints at the notion that cultural perceptions of time remain unfixed. As a Singaporean artist based in Berlin, the artist’s cultural identity has often been used in interpretation of his work. However, cinema is inherently “transnational” and is used by the artist to reveal the synthesis of cultures. In 明年| Next Year | L’Année Prochaine, this is most clearly viewed in post-colonial Shanghai’s “Western-style” Marienbad Café, where Wong’s cinematic language and conscious structuring of the film are emphasized.”

Excerpt from the UCCA exhibition text by curator Venus Lau.

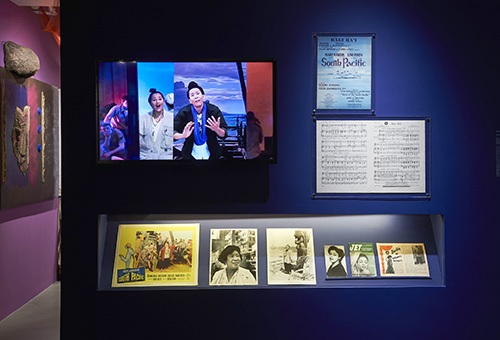

Installation shots, Passerelle Centre of Contemporary Art, Brest, France, 2016 :

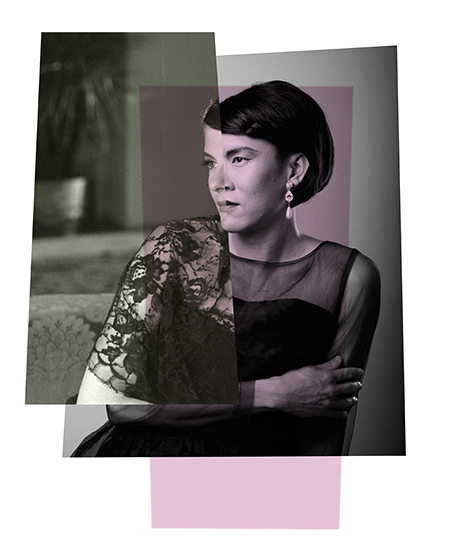

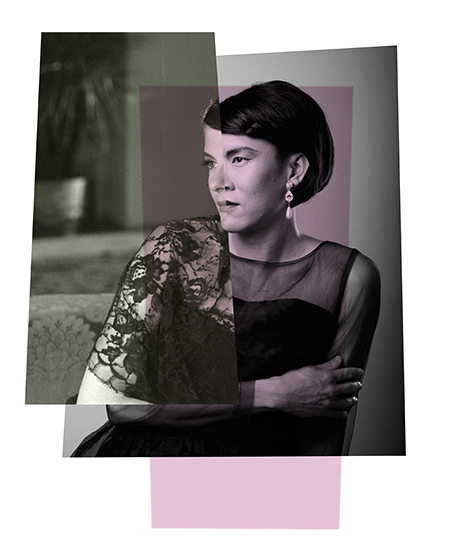

Portrait (Man) digital print 90x65cm:

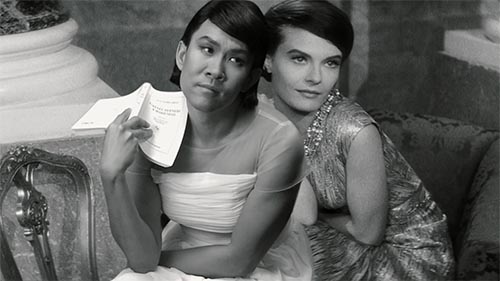

Portrait (Woman) digital print 90x65cm:

Portrait (I) digital print 50x40cm:

Lehre deutsch mit Petra von Kant / Teach German with Petra von Kant

Lehre deutsch mit Petra von Kant / Teach German with Petra von Kant

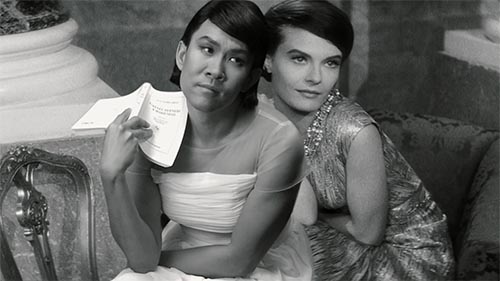

Aku Akan Bertahan / I Will Survive

Aku Akan Bertahan / I Will Survive

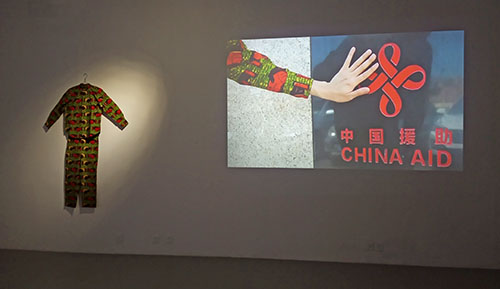

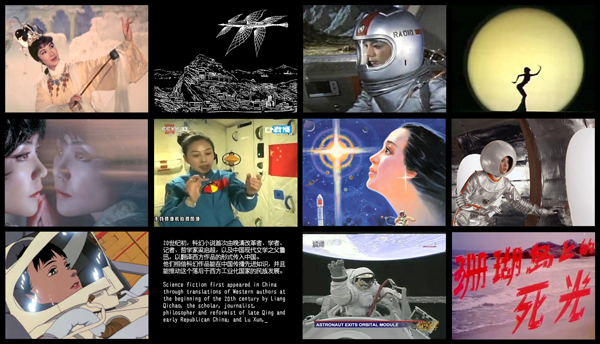

Scenography for a Chinese Science Fiction Opera / 中国科幻戏曲的舞台布景设计

Scenography for a Chinese Science Fiction Opera / 中国科幻戏曲的舞台布景设计

Windows On The World (Part 1) / 世界上的窗户(第一部份)

Windows On The World (Part 1) / 世界上的窗户(第一部份) Blast off into the Sinosphere

Blast off into the Sinosphere